Oil palms grow only in a tropical climate. This means that they are in direct competition with areas of rainforest, and that palm oil production is a major contributor to species extinction. The orang-utan and many other species are under threat as a result of rainforest destruction. For example, researchers at Queen Mary University of London found that the constant fragmentation and destruction of virgin forest for the creation of plantations is having disastrous consequences for bats. Oil palm cultivation is diminishing both the diversity of species and the genetic diversity within a species (Ecology Letters 2013).

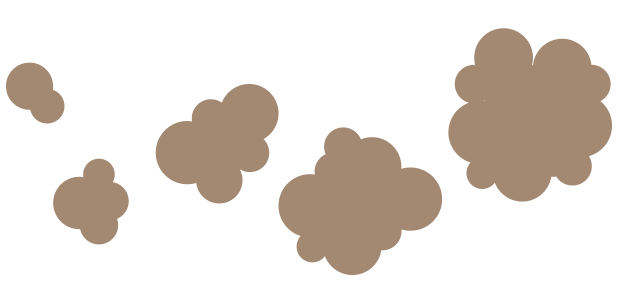

Rainforest destruction also increases the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. To make way for palm oil plantations, the forest is often cleared by slash-and-burn. Oil palms are frequently planted on peatland, which releases particularly large quantities of carbon dioxide when it is burned. NASA experts calculate that between August and October 2015 alone, these fires released up to 600 million tonnes of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere – a quantity higher than the equivalent to the annual emissions of Germany. As a result, Indonesia is among the 10 biggest emissions producers worldwide. Slash-and-burn practices are also harmful to health. In 2015 the smog that was created by the burning of the Indonesian rainforest was so thick that warnings of dangerous levels of air pollution were issued in Malaysia and Singapore. In November of that year, for example, the fires meant that the amount of particulate matter in the air in the Thai city of Songkhla was 365 micrograms per cubic metre – far in excess of the EU limit of 50 micrograms.

Reports from the plantation areas – especially in Indonesia – reveal that palm oil production often involves large-scale violation of human rights in the form of poor working conditions, social injustice and conflicts over land. Plantation workers and their families frequently live on the palm oil plantations, with no contact with life in the outside world. Indigenous peoples are often affected by oil palm cultivation: they may be evicted from their land and deprived of their livelihood. According to the Indonesian human rights commission, Komnas HAM, around 30 per cent of the 5,000 violations of human rights that were reported in Indonesia in 2010 were connected with the cultivation of palm oil.

Why is palm oil important despite its drawbacks?

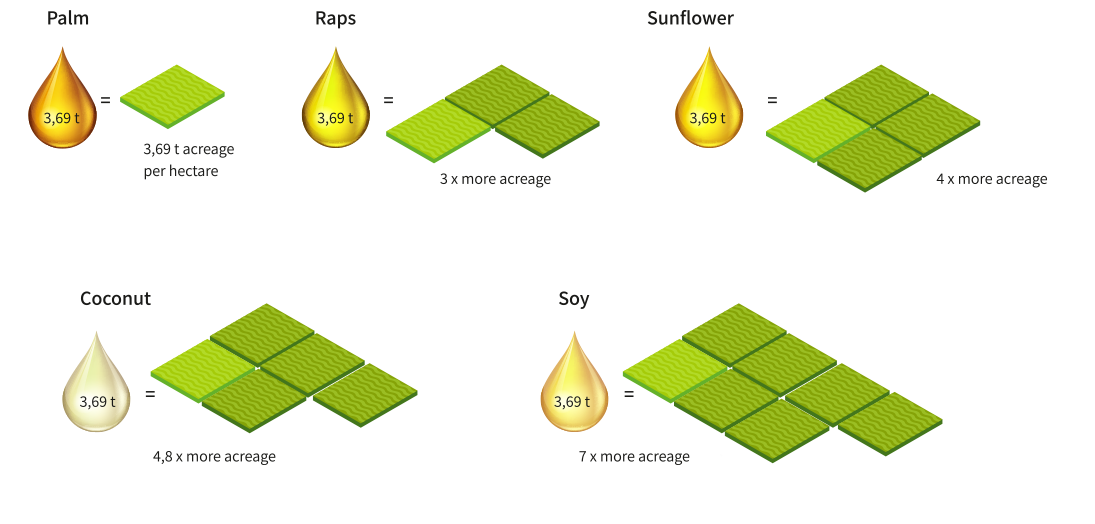

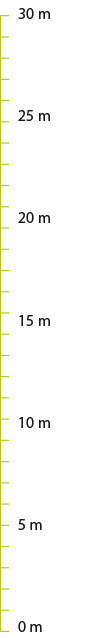

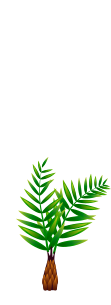

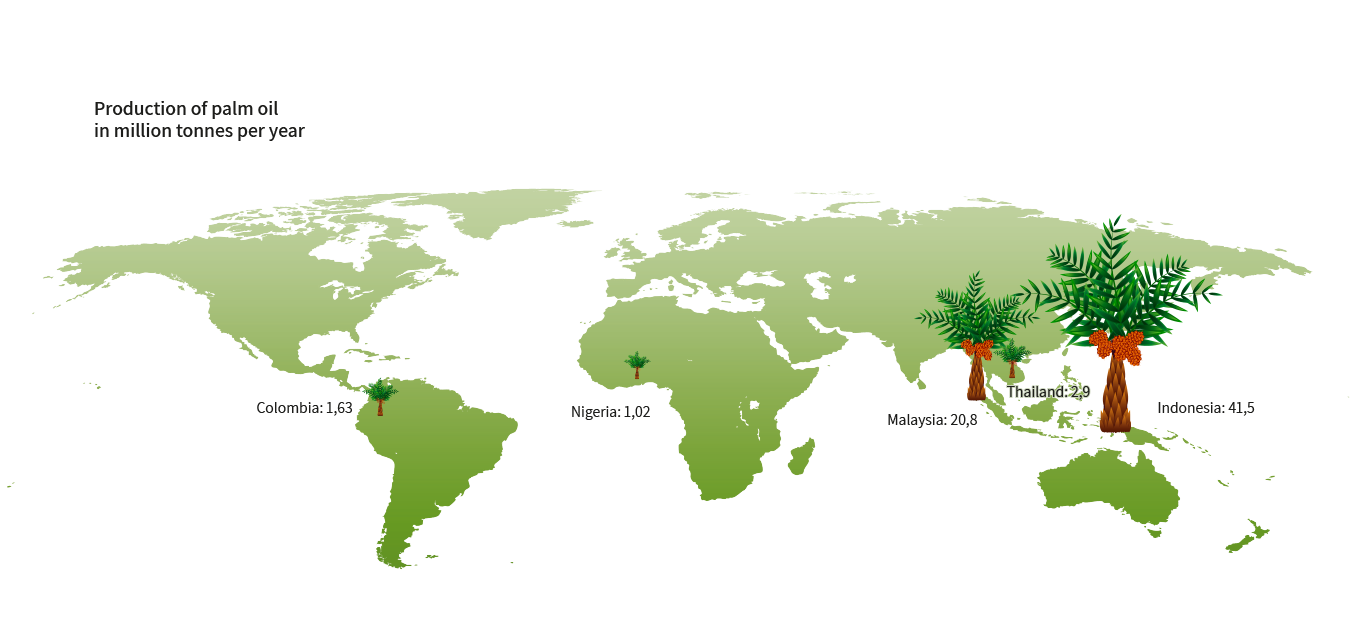

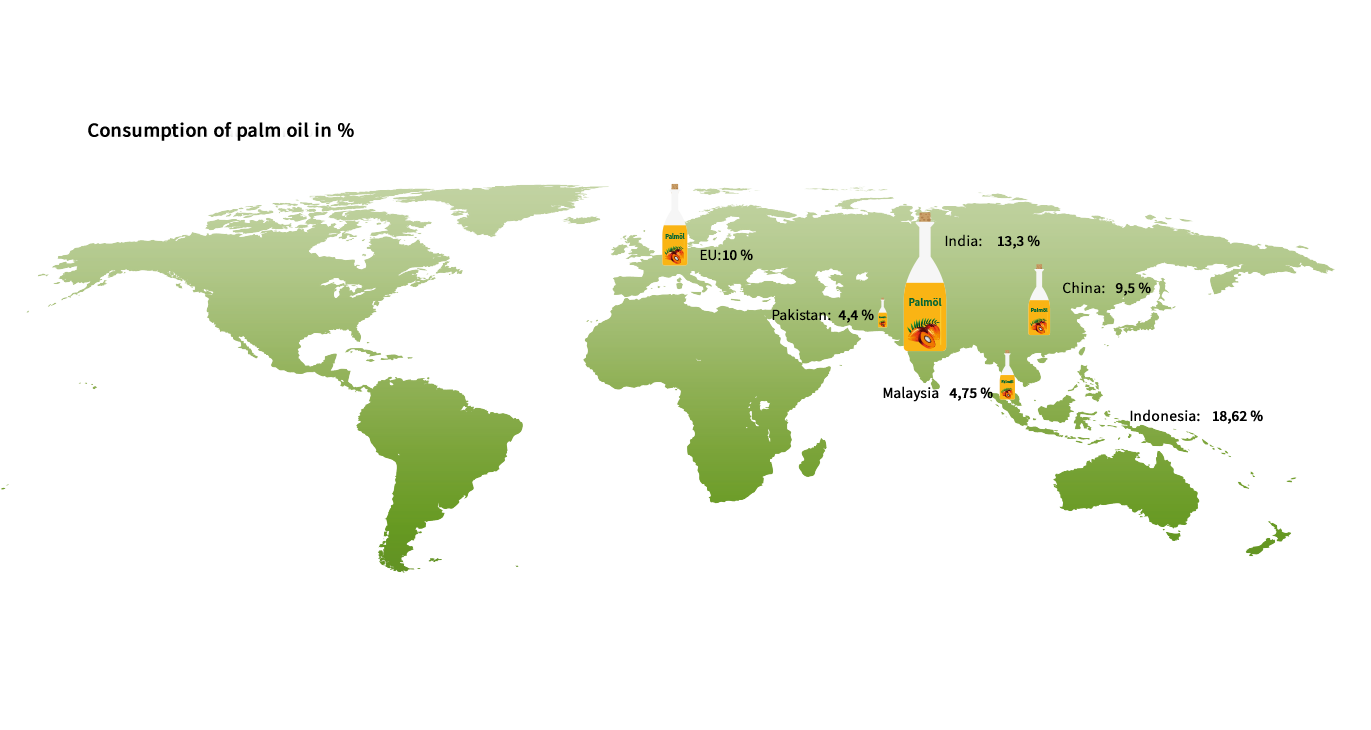

Despite this, a ban on the production of palm oil is not a viable solution. Oil palms occupy the smallest proportion of all the land that is used for oil and fat production while at the same time accounting for the largest proportion of worldwide vegetable oil production – 36 per cent (USDA, 2020). Sunflowers, coconut and soybeans all have a yield per hectare that is on average just one-third that of palm oil. Replacing palm oil with other vegetable oils would therefore not have the required effect, but would merely displace the problem and in some cases even make it worse. For example, soybeans and coconut grow in the same sensitive regions or in ecologically similar ones. Growing them would need more land; more greenhouse gas would be produced and more species would be put at risk. And the most important European vegetable oil, rape oil, would not be able to meet the rising global demand for plant-based oils.

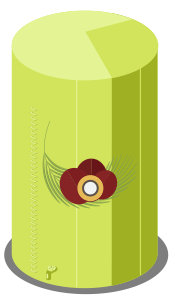

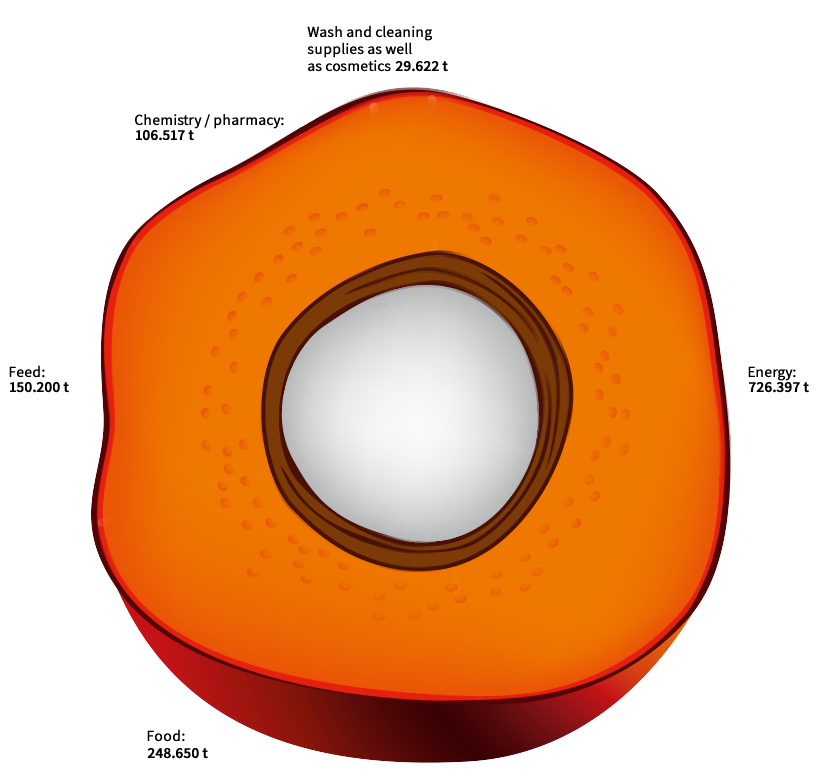

The high land efficiency of oil palms means that they have an important part to play in meeting the rising global demand for vegetable oils. And the oil palm is not only the world’s highest-yielding oil plant – it is also the only crop that yields two different oils that are useful to industry.

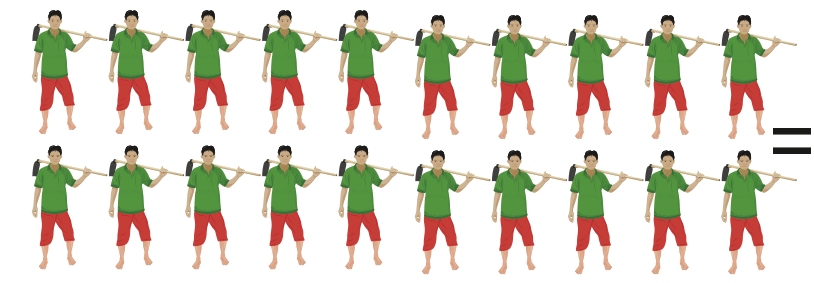

The production of palm oil is important to the economies of producer countries. The international trade in palm oil is a key source of revenue that can make an important contribution to economic growth. In addition, the non-mechanised harvesting of the palm fruit, which can be performed about 15 times a year, creates large numbers of jobs – many of them in rural and structurally weak regions.

4 t palm oil per hectare and year

Solutions and objectives

Oil palms are grown both on large plantations and on small family farms. Achieving the highest possible yield with the minimum detriment to nature is the challenge of sustainable cultivation. Because of the growing global demand for palm oil, more and more land is being converted to palm oil cultivation. Steps must be taken to ensure that this cultivation is sustainable and is carried out with respect for people and the environment in the countries and regions that are among the most biodiverse in the world.

The destruction of the rainforest is a problem that must be taken seriously and brought under control. As part of the search for a solution to the pressing problems and in response to international criticism of practices in the palm oil industry, various sustainability standards that involve certifying the production and use of sustainable palm oil have been set up in recent years. The certification systems include the first and most widely used scheme, the Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), as well as others such as the Rainforest Alliance, the Roundtable on Sustainable Biomaterials (RSB), and International Sustainability & Carbon Certification (ISCC).

Certification

Certification systems alone cannot solve the problems in the palm oil sector. The existing standards can be considered adequate in that they define minimum criteria for sustainable palm oil production.

These minimum standards include:

- No clearance of forest areas of high conservation value to make way for new plantations

- Environmentally sound production

- Respect for the rights of local communities

- Respect for workers’ rights

Nevertheless, all the certification schemes are in need of improvement, particularly with regard to transparency and specific requirements. The Forum for Sustainable Palm Oil and its members are therefore calling for further improvements, including:

- A ban on plantations on peatlands and other carbon-rich land

- A ban on the use of highly hazardous pesticides and paraquat

- The application of strict reduction targets for greenhouse gases

- A guarantee that, when certified palm oil mills purchase non-certified raw goods, these are obtained exclusively from legal cultivation

- More transparency in complaints procedures

Informing and networking – good reasons to join

Bringing about sustainable change in palm oil cultivation requires concerted action on the part of all stakeholders. FONAP is therefore not just an important dialogue platform. The Forum’s members also work together to change the impacts of conventional palm oil cultivation. Their activities include:

- Devising viable schemes to ensure that only certified palm oil, palm kernel oil and palm oil derivatives and fractions are supplied to and used in Germany, Austria and Switzerland.

- Preparing and distributing information on all aspects of sustainable palm oil production

- Drawing up proposals for improvement and refinement of the existing certification schemes.

- Networking with other initiatives and with interested companies and non-governmental organisations in Europe with the aim of working together on issues relating to the sustainable cultivation of palm oil.

Joining the Forum has many benefits for interested companies, NGOs and associations. Members have access to information on best practices and to a wealth of knowledge and experience. FONAP regularly runs training sessions and seminars for its members and it can provide information on preparing for certification. In addition, small and medium-sized companies have access to FONAP’s guidelines on the procurement of certified palm oil.

Mitglieder

Supporter

FORUM FOR SUSTAINABLE PALM OIL

Your direct contact

Secretariat of the Forum for Sustainable Palm Oilc/o GIZ GmbH, Andreas Knoell

Friedrich-Ebert-Allee 32+36, D-53113 Bonn

Telephone: +49 228 4460-3687

E-Mail: sekretariat@forumpalmoel.org

Promoted by

BMEL & FNR

.jpg)

.jpg)